“Dorothy Woodman, the Labour Party and me” or “how my grandmother came to England in 1935”

Those alarmed by the clamour for discipline and ideological purity within the Labour Party of late perhaps have short memories. In researching my family history - and particularly my grandmother’s arrival in England as a German teenager in 1935 - it has been fascinating to find out more about the dynamics and tensions within the Labour Party at this time amidst the growing concerns for fascism and between those in the party who - on the one hand - genuinely feared for Hitler’s ambitions in Europe and those - on the other - who wanted to enforce party discipline and were perhaps more fearful of the threat to the workers movement in Britain from Moscow.

A few years ago I wrote to the Labour History Archive and Study Centre (People's History Museum) to see if they had any records relating to my grandmother, Sonia Anderson (née Schreiner). As well as being a Labour town councillor for most of her adult life (until her death in 1998) she had come to the UK in 1935 as a refugee from Nazi Germany. Born in Stuttgart in 1920 her family had fled Berlin to Paris in 1933. Her father had been a prominent Communist and would certainly have been arrested and interred in one of the growing number of concentration camps in Germany. However after two years in Paris she was sent to England aged 15. The family story was that this was via the Red Cross but it seems more likely that this was through a connection in the Labour Party: Dorothy Woodman.

The Reichstag Fire

Dorothy Woodman was a socialist, activist and journalist. In 1933 she had been working in Berlin and covered the Reichstag fire; a significant event in the consolidation of Nazi power in Germany. At the time Hitler was Chancellor but the Nazi party had failed to form an overall majority government at the Federal elections the previous year. The fire at the Reichstag - the German parliamentary buildings in Berlin - was used by Hitler to apportion blame on the Communists in Germany and to legitimise a consolidation of power by the Nazi Party. The immediate outcome - brought into law the day after the fire - was the suspension of civil liberties as well as freedoms of expression and the press, the right to free assembly and the right to secrecy of post and telephone.

As a journalist in Berlin Woodman had managed to arrange an interview with the Russian communist Georgi Dimitrov, one of the Communist conspirators accused of organising the fire. On her return she was able to write about the impacts in Germany of fascism and the rising arrest and oppression of political opponents. It was in this context that she became co-secretary of the Relief Committee for Victims of Fascism whilst also running as a Labour Party candidate for Wood Green.

The Relief Committee for Victims of Fascism

Through the spring and summer of 1935 Woodman received several letters from the National Executive Committee of the Labour Party frustrated at her contributions to the Relief Committee and it is copies of these letters which the People's History Museum kindly copied and sent me when enquiring after my grandmother.

The role of the Relief Committee was three-fold: to raise funds to help those persecuted by fascism, to raise awareness of the growing threat of fascism in Germany and Spain within Britain, and to organise demonstrations amongst workers movements to show solidarity with the victims of fascism. In the summer of 1935 Woodman counter-signed a letter along with former Labour Party member and Trade Unionist Isabel Brown. The letter outlined with exacting detail the 296,257 political arrests there had been in Germany of workers, Jews and progressives along with the 132,544 injured and crippled in concentration camps and prisons whilst some 3,944 had been killed, either “shot whilst escaping”, suicided or “simply shot without explanation”.

In the piles of papers I received there is a back and forth between Woodman and Mr J Middleton - General Secretary of the Labour Party - emphasising the incompatibility of being a Labour Party member and supporting a cause considered to be subject to outside political influences. Woodman argues in her response that her work for the Relief Committee was widely supported by colleagues and was not incompatible with cooperation from Labour Party members with other parties in opposition to the Unemployment Act of 1934 or the British Colonies (Sedition) Act of 1935 (JSM/CP/104). However this argument fell on deaf ears and Woodman was instructed to cease further affiliation with the Relief Committee.

The Relief Committee was not without controversy and was to be proscribed as a “Communist front” by Clement Atlee later in 1935. But it’s sources - and fears - were felt to be valid and of genuine concern to the working class movement within Britain. And it had vocal support from a wide range of high profile figures within the country including Aldous Huxley, JB Priestley, the Dean of Canterbury Hewlett Johnson, the Bishop of Bradford Alfred Blunt and Dudley Aman, Lord Marley.

There was undoubteldy influence within the Committee from the Communist Party in Moscow, likely via funding through the German communist Willi Münzenberg in Paris. Münzenberg had founded the World Committee Against War and Fascism in Berlin in 1933 before fleeing to Paris where he took over the Editions du Carrefour press. It was in Paris that Münzenberg spearheaded the publication of numerous books warning against the dangers of fascism and Hitler’s ulterior motives for Germany, including several by my grandmother’s father, Albert Schreiner.

Münzenberg was a skilled writer and propagandist. He had been in regular contact with Moscow since the German Revolution of 1918 and worked closely with prominent left-wing writers in Germany such as Bertolt Brecht. In 1924 he launched the illustrated weekly AIZ, a popular socialist newspaper with a circulation of almost half a million before the Nazi's seizure of power.

Woodman, the Comintern and anti-fascist connections

In 1933 Münzenberg oversaw the publication of the Brown Book which proposed that it was in fact the Nazis that had been responsible for the Reichstag fire and not Communist agitators. Whilst it is now recognised that the book was largely a propaganda exercise it played a valuable role in raising awareness globally of the full extent of persecution carried out by the Nazi party as well as the threat to the Jewish population in Germany and the increasing use of concentration camps to imprison and punish political opponents.

To return to Woodman it is hard to say what her involvement was - if any - in the arrival of my grandmother in England. Certainly there was a groundswell of individuals wanting to provide refugee opportunities within Britain for both Jewish and non-Jewish refugees as noted by Hansard in this notice from Lord Marley in the House of Lords from Febuary 1935, notably some three years before the infamous Kindertransport operation of 1938-39.

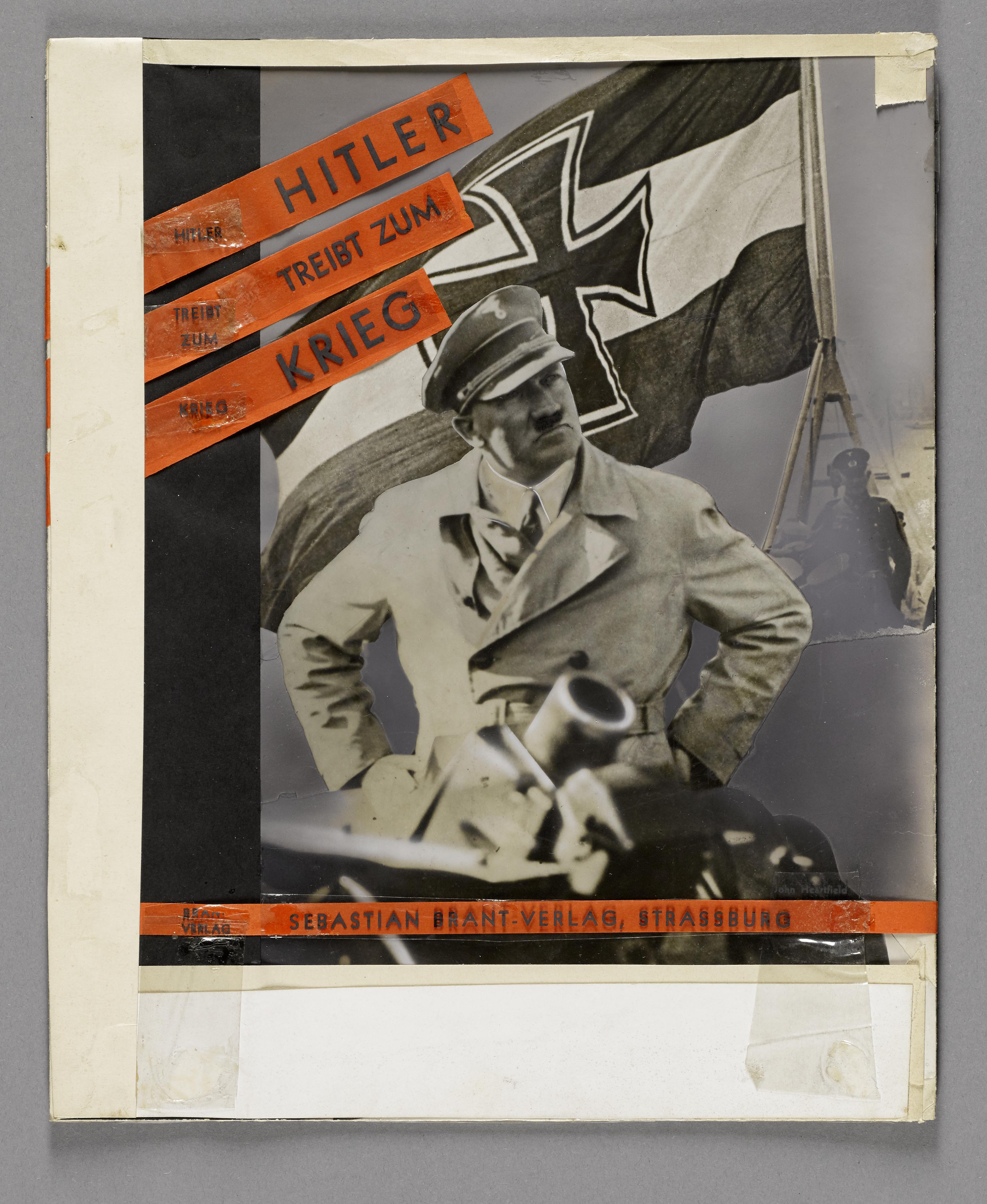

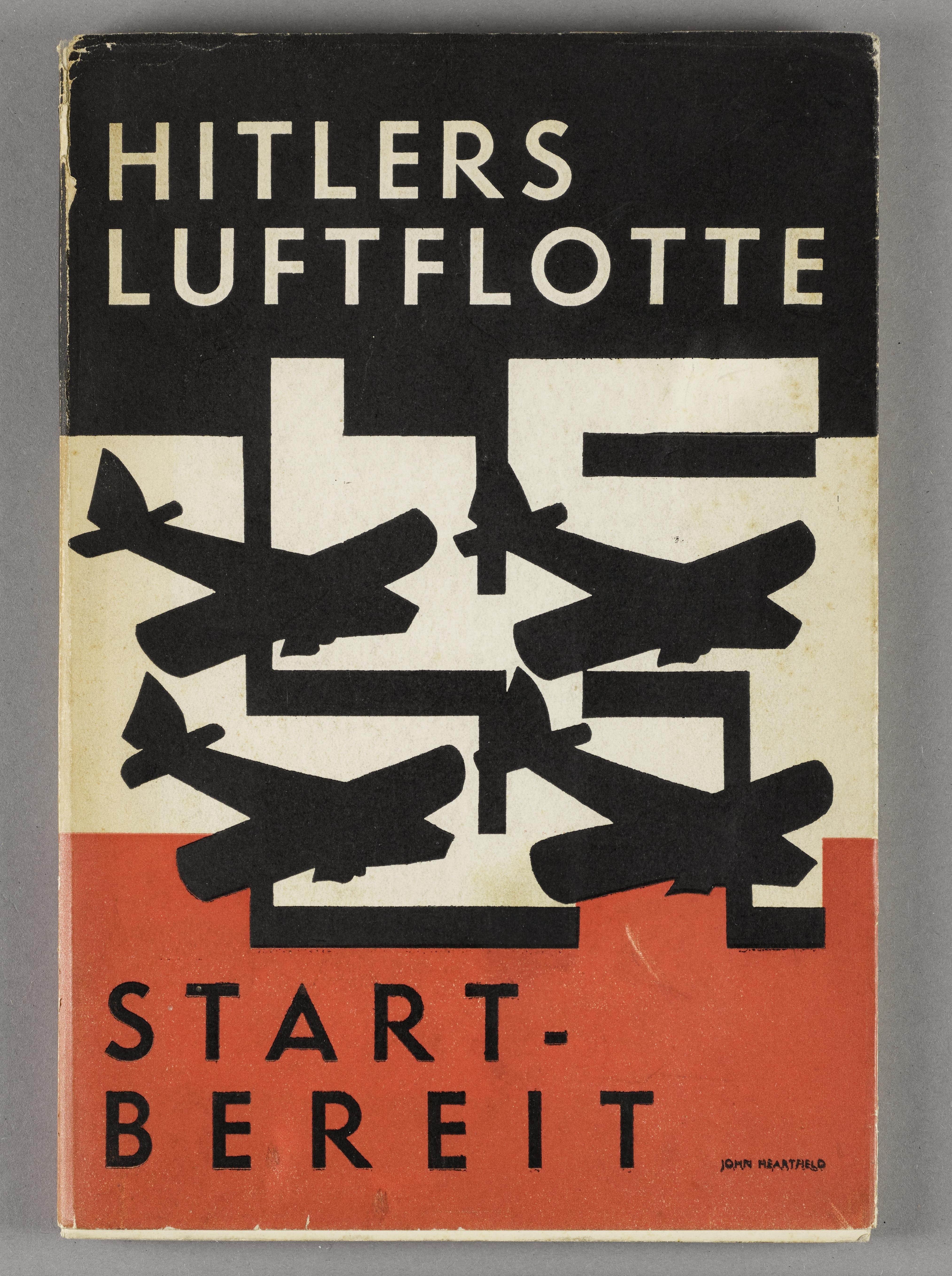

But it is important to note Woodman’s connections with the World Committee Against War and Fascism headed by Münzenberg. And it is in this context we have to look at one further connection in which my family is explicitly linked: the publication by Münzenberg in 1934 of “Hitler triebt zum Krieg” - “Hitler’s Drive to War” - published in German, French, Russian and English and in 1935 of “Hitlers Luftflotte startbereit” - “Hitler’s Air Force ready for take off” published in German, French and Russian. What is of interest with these two books is that they were both written by my great-grandfather Albert Schreiner but both had been released under the name of Dorothy Woodman.

Both books warned about Hitler’s plans to mobilise for war in Europe and - like the Brown Book - had sought to warn western countries of the genuine threats posed by National Socialism to European peace. Of course these were in part politically motivated by the aspirations of the Comintern (Communist International) in Moscow. But they were also largely organised by anti-fascists from Germany that had seen what Hitler was capable of and wanted to send a warning to others about what might follow. In his comprehensive book on the German anti-fascists in exile - Weimar in Exile - Palmier comments on these books:

“it is such a mine of information that it is hard to understand how the émigrés managed to obitain it all” (p327) and that the Nazi’s war preparations were - from the benefit of hindsight - written with “astonishing precision.” (p)

Although both books were written under the name of Dorothy Woodman it is now largely recognised that her name was primarily used to reach a broader audience and help legitimise the messages in the book to a non-German audience. Indeed it was quite common for German exiles to use publish under a pen name (in a subsequent book Albert published under the psuedonym “Albert Muller” and he was to go on to fight in the Spanish Civil War under the nom de guerre “Albert ‘Juan Pena’ Schindler”). Certainly Woodman’s journalist credentials as well as her connections to the Labour Party and also the Relief Committee would have helped spread the message to concerned ears in Britain and got it to the right people that could do something about it. She certainly had the ear of influencial figures such as the aforementioned deputy speaker of the House of Lords, Lord Marley.

Family Ties

But perhaps the greatest clue lies in the words of Albert himself who in his lebenslauf, written shortly before his death in 1979:

“Meine Tochter Sonia, geb 5. Marz 1920, ist in England verheiratet. Wir haben sie 1935 durch Varmittlung von Parteifreunden in England untergebracht, damit sie ihre Ausbildung fortsetzen konnte.”

“My daughter Sonja, born on March 5, 1920, is married in England. We placed her in England in 1935 through the mediation of party friends so that she could continue her education.”

So it is perhaps not a huge leap of faith to suggest that the close connections between Dorothy Woodman and Münzenberg had provided a means to get my grandmother out of Paris, especially since it is known that the former had visited Paris in April of 1935 to attend an International Conference reporting on the persecution of workers and socialists in Spain following the failed Revolutionary General Strike of 1934.

After defeat in the 1935 election Woodman gave up on her political aspirations but continued to write and champion socialist causes as secretary of the Union of Democratic Control. She was in an open relationship with the editor of the New Statesman - Kingsley Martin - and became their Asia correspondent, going on to write a book about anti-colonial struggles in Burma and the imperial wrestle for control of the Himalayas.

In 1949 the author and fellow New Statesman journalist George Orwell had given the British secret services a blacklist of “cryptocommunists and fellow-travellers … who should not be trusted as propagandists”. However, despite her clear connections with the activities of the Comintern - notably in those years preceding the outbreak of World War II - she can at best perhaps be regarded as a “near-Communist”. Regardless, she was a key figure in raising awareness in Britain of the dangers posed by the Nazi party, a prominent anti-fascist and anti-imperialist, a reassuring thorn in the side of the contemporary Labour Party and a proud left-wing agitator.

I’ll likely never know for certain if it is through Woodman that my grandmother came to England in 1935. But it’s a good story nonetheless. And if anyone can find a picture of Dorothy I’d love to see it - struggling to find one on the internet.